I just do what I want and I’m a kid in a candy shop. Vladimír 518

Text: Nikolas Bernáth, photo: Tibor Czitó

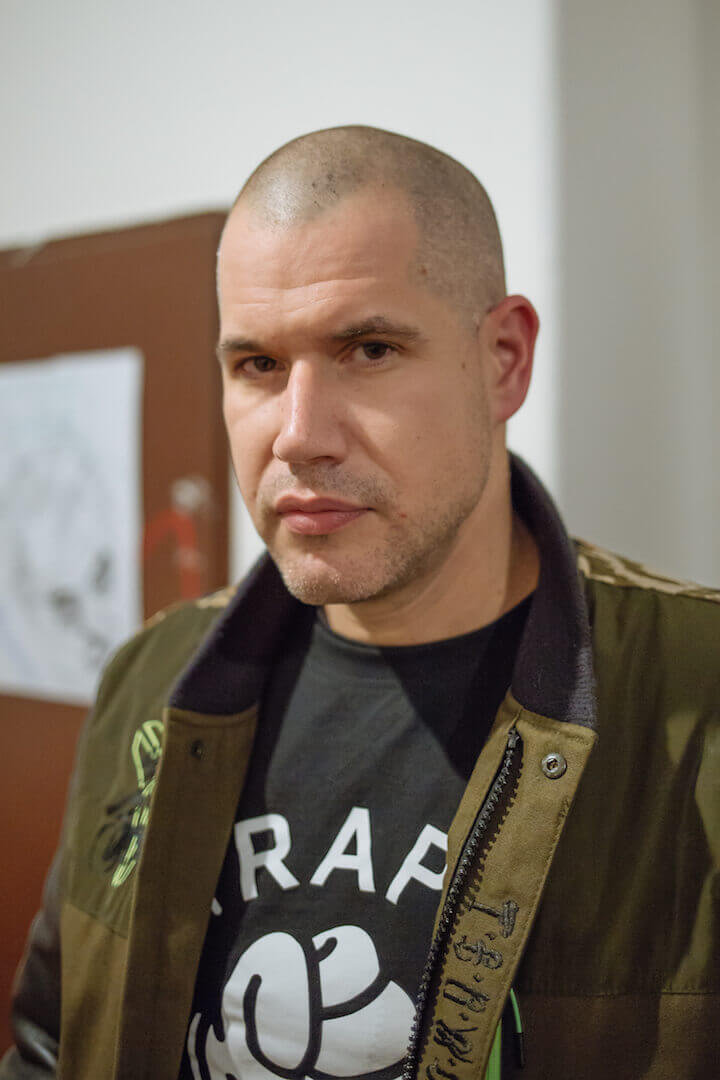

Vladimír 518 is a well-known artist, rapper, publisher and a promoter of architecture. In Košice, we visited the community cultural centre KLUB. Moreover, it was originally inspired by squatting, which is a theme close to Vladimír’s heart. Years ago, he spent several years living in the famous Ladronka squat in Prague. The next day we picked him up at Invisible Hotel and took an architectural tour of Czechoslovak architecture from the second half of 20th century.

Your journey from heavy metal music, through graffiti to rap is well-known. At what point did you become professionally interested in cities, urban planning and architecture?

V: As far as urban planning and architecture are concerned, that evolved gradually from my interest in graffiti, heavy metal music and just music in general, clubs and social networks. That’s the sort of thing that teenagers are into. In my case, the main motivation was to meet the right people, buy the right magazines. In the early 1990s there was no internet, so gradually, the network would start taking shape in your mind and once you joined it yourself and became a part of the network, a fan turned into a creator. That doesn’t mean I stopped being a fan at that point. I’m a fan first and foremost, a child that wanders around, exploring the world. On the other hand, remaining in the position of a passive consumer wasn’t for me and I kept thinking I could do it as well.

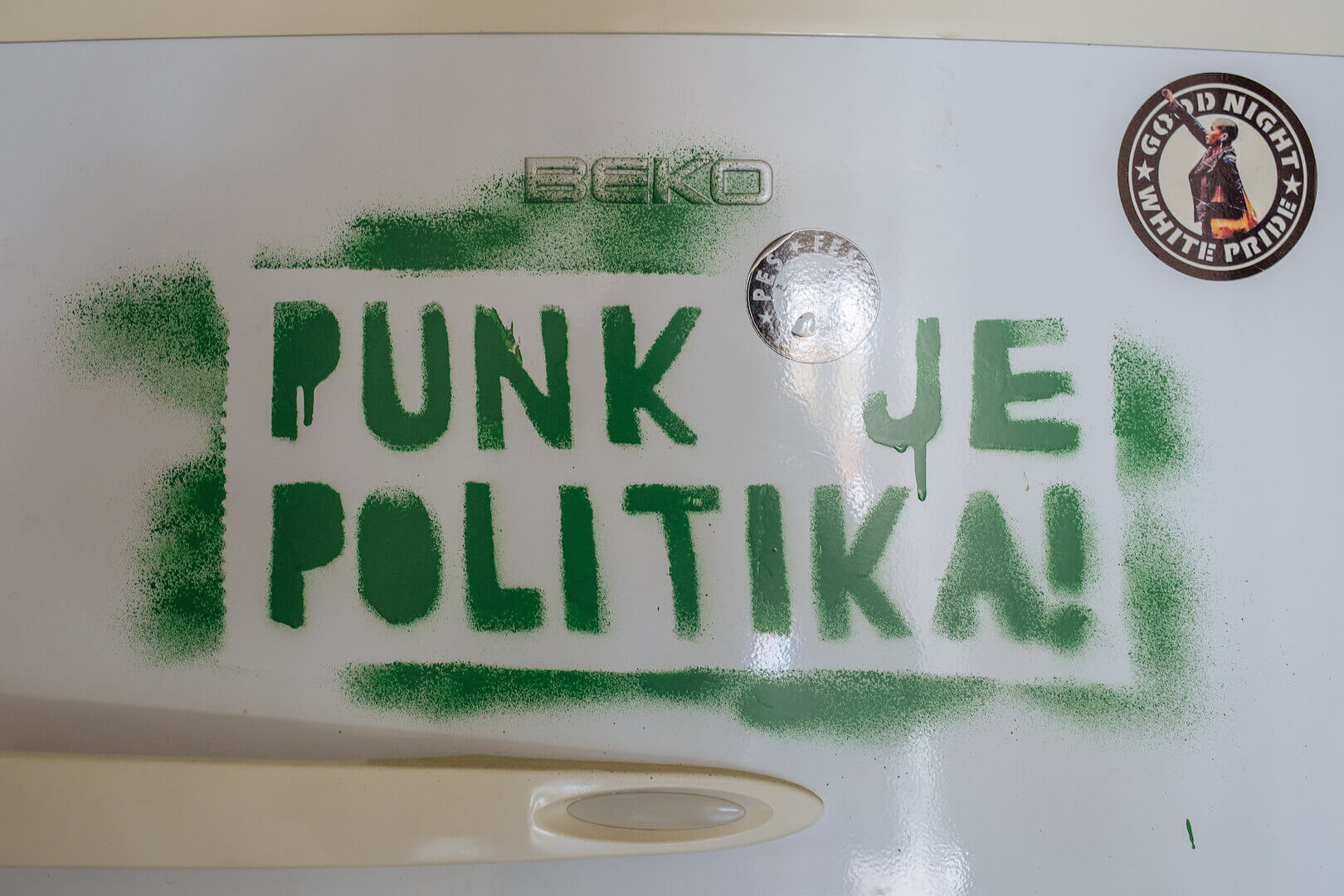

I’ve always seen my creative activities as research. The reason I wanted to have a magazine was to get to know the people behind it and, one day, create my own. That answers your question about when I became interested in architecture. Right at the beginning. My first encounter with an alternative group went hand in hand with analysis and my own work. First, it was the heavy metal subculture, then hard core, graffiti, rap and the rest followed. I started moving between various subcultures — theatre, skinhead friends, punk friends, tech friends, then squat, graffiti and so on. Then it all comes together and the next thing you know, you’re an urban explorer working on a project. Because putting information together means transforming it into a project of your own.

Unlike subcultures, architecture is very much in the public eye and is often considered the mother of all arts. People may find it surprising that a former squatter, graffiti artist and rapper also lectures about architecture.

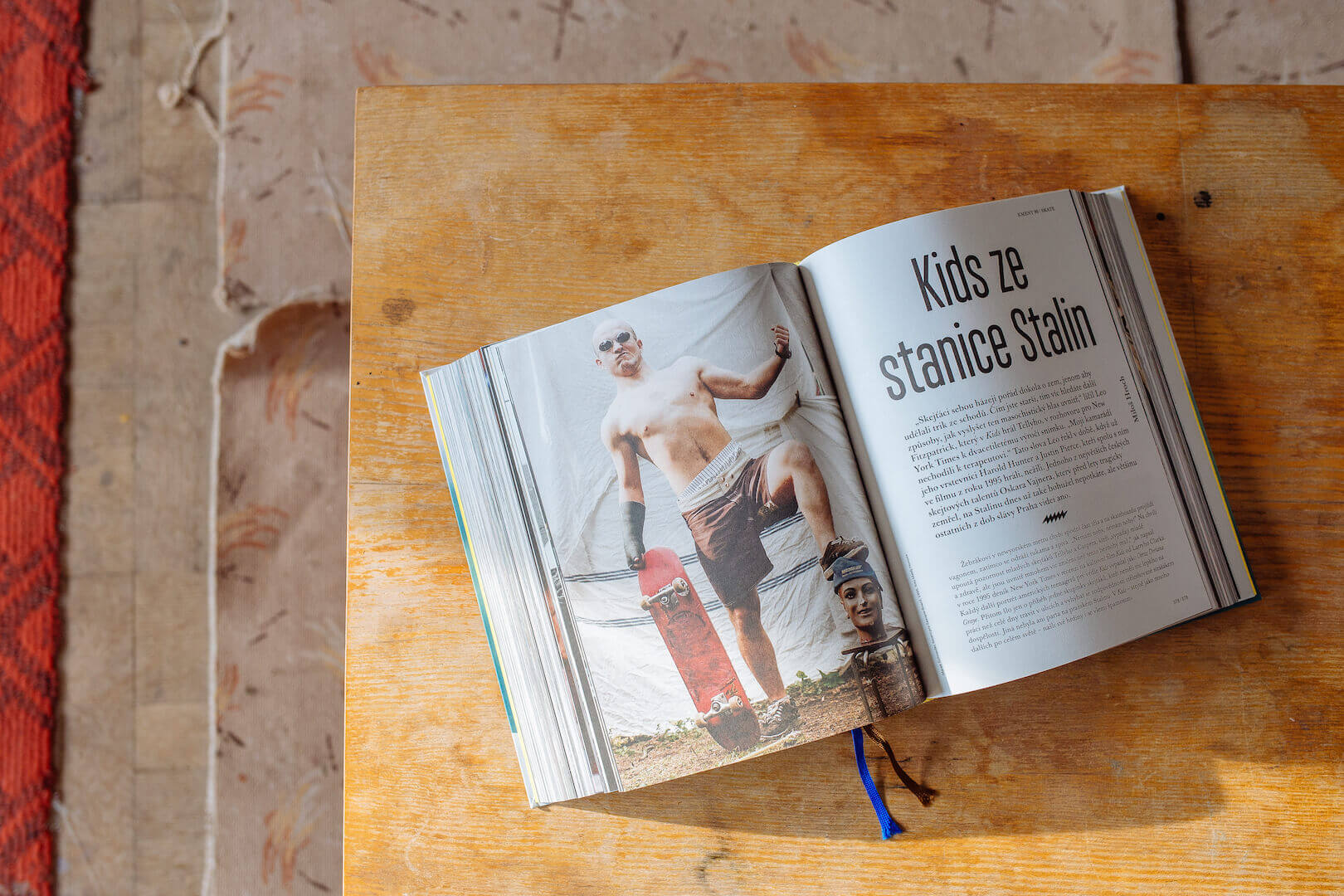

V: I’ve always been interested in combining the high and the low and for me personally, I believe that’s where the inspiration comes from. Architecture is definitely complex, it’s the ultimate discipline that combines all the others. My journey from the primitive, low genre of graffiti to architecture in urban context was a very natural one. My generation of graffiti writers was attracted to architecture, which is understandable. Being a parasite on a system makes you interested in your host and at one point you realise that the host is in fact quite fascinating. Driving a bus or tram around the city, scanning its layout, I looked up and all of a sudden, I saw a whole new world. That happened not only to me but also to many others on the graffiti scene. Some became architects, others idiots, artists, film editors, directors, cameramen or junkies. But our generation as a whole understood that the city is a very powerful element and, even more importantly, that architecture is based on the same principles as graffiti.

I’ve always been interested in combining the high and the low and for me personally, I believe that’s where the inspiration comes from.

Of course, we stated off naïve and immature, thinking we were somehow special. But that’s something all the young people have to go through. As a teenager you believe you’ve discovered something extraordinary that everyone will follow from now on. Then you realise your father and grandfather knew it already but still, you have to work it out yourself and you may realise that your way of discovering the same truth is through graffiti. You start communicating through shapes, letters placed around the city, as a surprise within the urban environment. Architecture does the same, which is why it captured our interest. Finding my way to architecture from such an unusual starting point gave me a fresh, interesting point of view which at the time was not common at all. Things used to be different when I was 20 and it was probably my pure love for architecture which won me acceptance among architects and helped me build friendships.

Do you believe that the public still tends to underestimate subcultures?

V: Definitely. But there’s some advantage of being underestimated. I’ve made good use of that position my whole life. People see me as a mere rapper but don’t expect me to have in- depth knowledge. On the other hand, subcultures are not taken seriously for legitimate reasons. They’re not complex but very limited, mere subsets of the big culture. I like genres, subcultures and I understand why they exist but I can’t accept their orthodox attitude. It’s very limiting and not loving it to death means not believing in it. An orthodox member of the heavy metal subculture or an orthodox anarchist misses out on the rest of the spectrum. People who inspire me more than the ones tied to a specific genre are the ones who were able to transcend their own subculture and think globally, see culture in its complexity. And that’s the type of thinking I’m interested in.

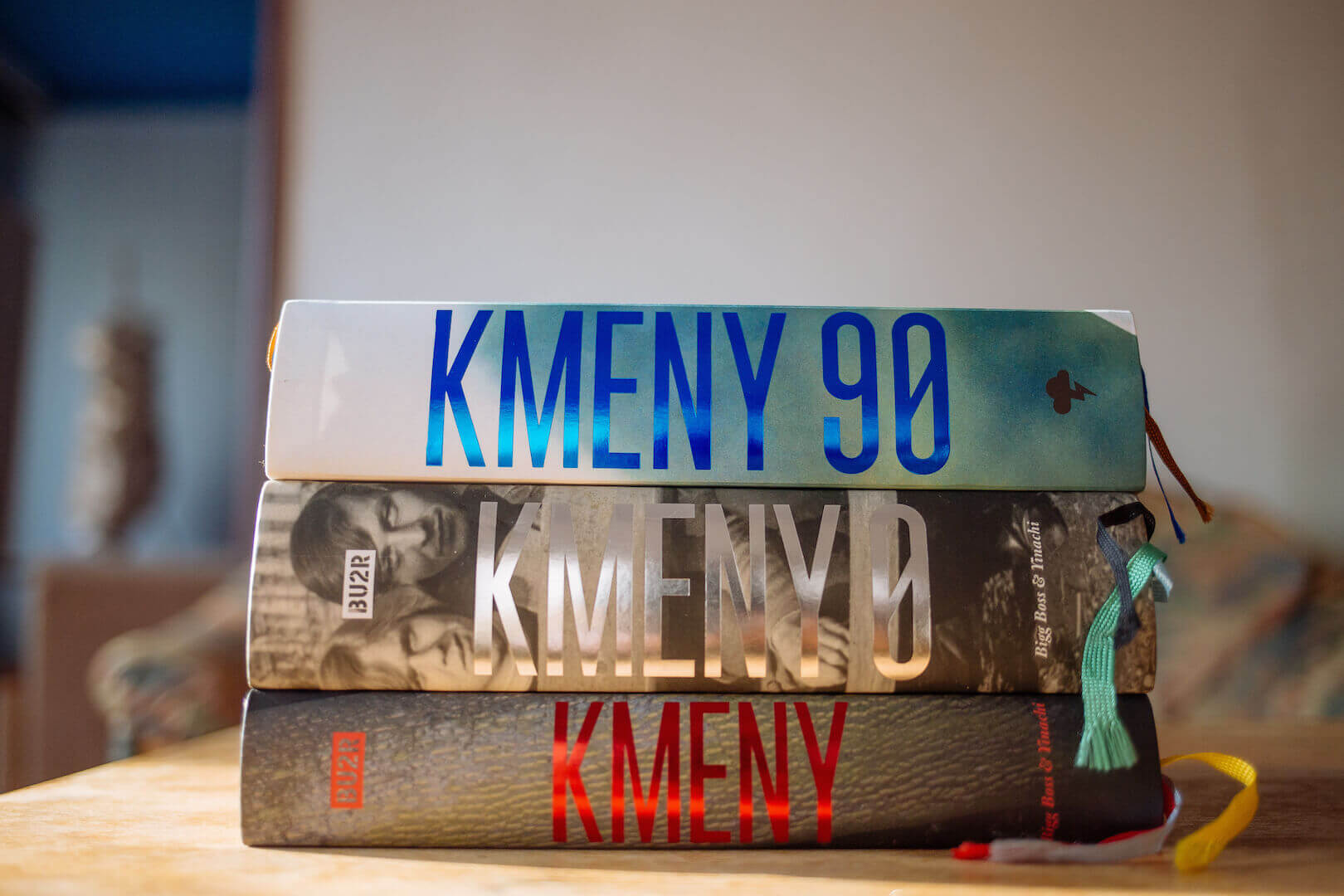

V: Sure. The motivation is my love for the subject and yes, my primary target audience is the crowd. It’s a book about the biology of culture and its species, an encyclopaedia of nature, which documents all the aspects and colours of culture. But the most important goal of the project is to show people that the differences we see in fact mean symbiosis. One person works out, another one wears black or other colours but it means that everyone is searching for the same thing. Differences unite us, because we are very much alike. While working on those books, I was reminded again and again how much I can identify with the subcultures’ leaders because we are all the same. They might not even be aware of how similar their principles are, which to me is the most intriguing aspect of all. And when you meet 25 leaders in a year, you realise that they’re all the same, which is great.

The last book in the series talks abut the 1990s. Would you say you succeeded in creating a complex image of the era?

V: We used to joke that the 1990s were about Bulgarians playing Americans. That’s what the 90s are to me. If I’d put on this jacket and sunglasses back then, I’d have felt like I’d discovered something new. But then you realise it’s not that simple and you have to hide behind the jacket, shoes, squat and all the other symbols and start reading between the lines. So that’s what 1990s mean to me — Bulgarian Americans.

Your most recent contribution to this project was not a book, though, but an exhibition in the Moravian Gallery. Years ago, when you started doing graffiti, you probably didn’t expect to curate an exhibition in a national gallery one day.

V: I didn’t expect two thirds of my life to turn out the way they did. When I was about 8 years old, I had this strange experience that I can still remember vividly. I’m walking in a forest experiencing something that later happened. I’m not talking about predisposition but I could feel the potential within me, even though I had no idea what to do with it yet. I definitely couldn’t imagine huge projects such as the Moravian Gallery exhibition but, oddly enough, every step seems to come naturally. I don’t feel like I’ve done something interesting or achieved something special because there’s very little difference between that little boy and the guy sitting here today. I still feel like a little boy and don‘t take my success too seriously, because I know that I can’t take credit for it. I was simply made that way but that doesn’t mean that I’m better than someone else who wasn’t. But I just don’t take things too seriously. My motivation for doings things is that I like doing them.

How did you feel about curating the exhibition? Did you take the same intuitive approach?

V: I do things intuitively but at the same time, I think a lot about them. Analysing things and looking for mechanisms that drive them is what I enjoy. What it means to fill the gallery space, convey a message, select pieces that speak for themselves and so on. It’s all research, just like the heavy metal zines. Yes, I’m very grateful for the chance to organise my own exhibition but it’s still my research and knowing all that I know now, as a result of that exhibition, is the greatest benefit. I spent a lot of time thinking about every single piece that I selected and had installed and it changed me. Even though I didn’t earn a single penny, because I put all the money back into the project, this exhibition made me realise one important thing. First, I was wondering whether I was going completely nuts. But then it hit me that had I actually earned any money, I’d have spent it anyway but this experience will stay with me forever.

You have a really wide range of activities and it keeps growing. Does it all come together in your mind, forming one big picture?

V: My strategy is not being career oriented at all. Working on your career means focusing on one thing and becoming very successful. In the end, that’s what everyone will identify you with. I’m not saying that’s a bad strategy and it’s better than mine in many ways but I prefer to travel and do research. Everyone needs to find their own way and this happens to be mine. Naturally, it all comes together in my mind, otherwise there would be no point in doing it. I’m fascinated by the similarities that all the mechanisms share. To put it simply, I do what I enjoy, like a kid stuffing himself silly with sweets. You know it’s not the right thing to do and I know it as well. I’ve always considered myself an artist and it would’ve been proper for me to spend my whole life painting, immersing myself deeply in visual art. But life happens and I choose to go with the flow. In the end, it doesn’t really matter. I’m just a child stuffing myself silly with sweets and I don’t really care about the consequences.

Let’s go back to architecture. What do you believe is the greatest challenge that cities currently face?

V: That’s very simple. In my opinion, it‘s the undeniability of historical layers. And it’s also vital not to lose because right now we are losing to the huge amount of misinformation, which wipes out a part of our memory. That’s what happens when a person with no education in terms of art and culture grows up with parents who did have that education. When they pass away, this person ends up throwing all the beautiful 1960s designer furniture, sculptures and paintings away and replacing them with XXXLutz. My message to that family is: you have some beautiful furniture, don’t throw it away, because the replacement you get at XXXLutz is of much lower quality and cultural significance. That’s the greatest challenge we have to face in order to save architecture.

It’s also vital not to lose because right now we are losing to the huge amount of misinformation, which wipes out a part of our memory.

As far as the city as a whole is concerned, it’s essential hat we stop being afraid, accept the city life, love it and shape the city in order to enjoy and understand it. There’s been a lot of discussion about how to make our city a better place for life. There should definitely be more trees and benches should look better but the most important thing of all is to understand the city. Once you understand it from the perspective of urban planning, you’ll see its layers, understand why that house looks the way it does and what era it dates back to. And that means more than having a bench or a dustbin.

It’s often said that people who live in Košice feel closer to Prague than Bratislava or any other city. Is that really the case or is it a one-sided relationship?

V: My answer is yes but if you asked an average person from Prague, their answer would be no. Historically, those close ties have always been there, thanks to people like you and me. A lady living here and one living in Prague don‘t know or care about each other but we do. It’s always been like that and always will be. Those ties are real and it’s good to have them.

Come to see the art of Vladimír 518 while staying at The Invisible Hotel. Book your room now.