Inner potential of Košice’s South

The large areas of Košice that lie below Námestie osloboditeľov (Liberators Square; below meaning to the south / opposite direction from where Main Street begins) unfairly receive significantly less attention and care than the coveted Sever (which means North) which with its structure, density, street language and walkability can, with eyes squinted and some imagination, satiate our needs for a local Brooklyn.

The injustice of the position of Juh (which means South) is rooted in historical development, recent expansion, and the gradual shift of the geographic centre to the south. The fortification system of walls, gates and bastions originally extended to the Lower Gate at the southern edge of the medieval city. This was in the area of today’s chaotic crossroads (or cluttered traffic junction), which we inevitably call a square, and this system was complemented by a citadel, which was rediscovered a few years ago during the construction of a shopping centre. Everything below (meaning south of where Main Street begins) has for centuries been encoded in the mental map as South or as suburbs.

Railways

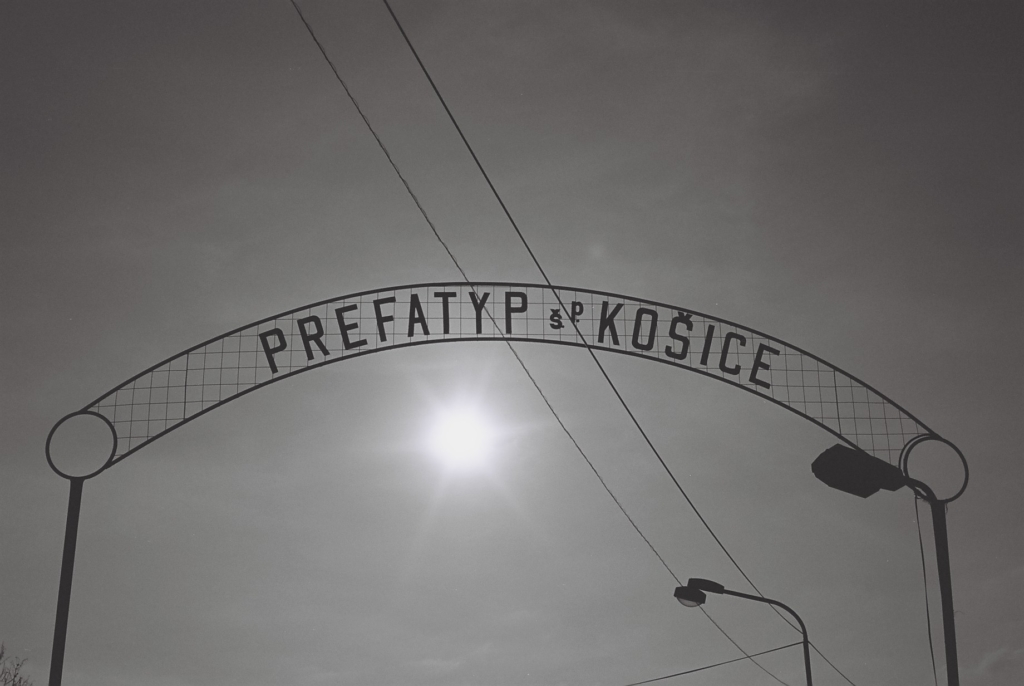

For example, the train stop at the railway depot is called Košice predmestie (suburb). Just as the housing estates begin to spread out beyond the historic centre to the south, at the junction of a four-lane road, a rough bundle of sidings and a locomotive depot, there is a small gated house with barriers, a couple of benches and an information board. A place somewhat similar to the cultural centre Stanica in Žilina-Záriečie provides a view to the south, because in these places the railway crosses the town in an infinite straight line. Does that sound like a description of a periphery? Maybe a little, or more than a little, but it’s still a place within a fifteen-minute slow walk of Main Street.

The south of the city is relatively rich in tracks, stops and stations. When you follow the railroad, above (meaning further north of) the (main) train station, you will find a beautiful bridge above the Hornád River (this particular above means that an object is located above another object), a station in the village of Ťahanovce and a tunnel at the end of the village. To the south the tracks branch out into many sidings and several southern outposts below the city of Košice.

One of them is Barca, a historical village that was administratively attached to Košice and gradually began to merge with the city. The tram line, which takes tram number four to Barca (and tram number seven from Barca), is a little further away from the centre of the district but the train station is even further to the east. The station might be closer for some residents of the Nad Jazerom housing estate than some of the residents of Barca. The station is characterised by its rectangular shape and generous use of concrete. Its best days are over, but it still serves passenger trains that go to Moldava and Turňa – both of these places bear the denomination above the Bodva River. Several platforms and an underpass leading to the other side towards the large abandoned factories in Košice provide a hint of the former big plans and lively traffic.

Close to Barca station, on the southeastern line directly behind the large former mill and meat factory at the end of Napájadlá, is an unmarked structure, the size and shape of a medium-sized bus stop from the 1970s or 1980s. However, in the rear of the plant there was not a bus stop but an inspection depot. Once there were tracks leading to it, their fresh demolition over a long stretch perhaps indicating the beginnings of change in the neighbourhood. The buildings of the former mill, representing a monumental local equivalent of Michigan Central Station (a beautiful, long-abandoned train station in Detroit, considered one of the greatest ruins in the northern hemisphere), are after years of immobility (real estate can’t move, after all) and inactivity undergoing radical rather than cosmetic alterations.

The next district in this small southern triangle is Krásna – another historic village that has been consumed by the growing city. The district of Krásna still bears the old name Krásna nad Hornádom. The historic building on the very edge of what was once a village is surrounded with industrial yards and complexes. It is peculiar to see locals getting on and off the train here – getting to the first houses in the tangle of fences and desolate roads is not easy. The station is characterised by a huge number of flowers and plants in the waiting area. The botanical garden at the other end of the city has a strong rival in Krásna. There is documentation suggesting that there were plans to make this station more accessible by extending the tram line from Nad Jazerom and terminating in Krásna rather than in one of the current stations (Bajkal / Važec / Važecká).

Sites along the railways

We can learn from old timetables that passenger trains also stopped in Šebastovce. This miniature district had its direct rail connection with the city centre until 1986. Along with the connection the station also disappeared, the location of which can be clearly seen and felt from the overpass over the line at the northern end of the village. The current dramatic changes in the area around the villages below the southern boundary of the city due to the construction of the car factory inspired thoughts as to whether it might be appropriate to extend the tram line from Barca in this direction. Whether to stretch hundreds of metres, maybe even kilometres, of track, or rebuild the station? It is admirable that this battle has no clear winner. In any case, the aforementioned road overpass does not only offer a view of the village of Šebastovce and its theoretical future (former retrofuturist) station. A simple turn to the other side offers views of the south part of Košice, with all the blocks of flats of the Nad Jazerom district, as well as the now non-existent (but still easily imagined) row of trees on Slanecká cesta and the tops of the chimneys of the incinerator and heating plant.

It is clear from the multitude of industrial and technical buildings connected by kilometres and tons of rails that the south of the city has been assigned in the life of the city functions that differ from the historic centre, the urbanised north and the de-urbanised concrete satellite towns built on the slopes and in the hills of the basin that encircles the city and naturally opens it up to the south.

Connecting places by the railways

But why such a strong railroad and track accent that seems almost fetish-like?

Cities around the world have long developed along linear transport rail arteries and radial routes and, of course, in the proximity of entire systems. This is because they help to cover even large distances between the periphery and the centre in a relatively quick time (considering how far away the periphery can be located). This was the way Great Britain and its cities developed almost two hundred years ago, as well as the United States and its states and cities, and Austria-Hungary, the infrastructural legacy of which we use to this day.

Large cities in our area and in our socio-economic regional context are successful in their development mainly because of the easy access to their territory for large numbers of inhabitants. In recent years, new metro lines have opened up or existing lines were significantly extended in Budapest, Prague and Warsaw; moreover, Prague is continuously upgrading its tram line network, and the main station in Vienna has been hidden underground to give the opportunity for a new district to emerge on the surface in the place of kilometres of tracks.

Smaller and larger cities with overhead, underground, and even ground-level lines are building residential buildings, university campuses, and office space along their tracks. People are able to live in them and turn the proximity of the tracks into an advantage of quick and easy access to the whole city.

A city of a quarter of a million people could boast a very extensive network of railways, but Košice also has a parallel rail organism – the oldest tram network in the country. From its beginnings until the 1960s, it served not only passengers but also supplied the city’s factories and plants at night. The legacy of dismantled tram lines and sidings heading to factories in urban areas is as great as the current existing network. The nervous system of Košice, composed of rails, railroad ties and overhead lines, has a different topography from the traditional image of the city. Despite this, the stations and stops in and around Košice have the potential to become a network of suburban metro lines.

Potential for connecting places along the rails

The ninth paragraph of this text reads:

It is clear from the multitude of industrial and technical buildings connected by kilometres and tons of rails that the south of the city has been assigned in the life of the city functions that differ from the historic centre, the urbanised north and the de-urbanised concrete satellite towns built on the slopes and in the hills of the basin that encircles the city and naturally opens it up to the south.

The end of the third paragraph of this text reads:

Does that sound like a description of a periphery? Maybe a little, or more than a little, but it’s still a place within a fifteen-minute slow walk of Main Street.

The South is dotted with neglected areas that have lost their function or had their stories concluded in the recent or even distant past. But it is the proximity to the tracks and rail lines that gives them great potential for a new life. Many places, not only within the territory of the city of Košice, can be fifteen minutes away from Main (railway) Street (station). It doesn’t have to be a slow walk but, for example, a brisk train ride.

Invisible Mag is supported using public funding by Slovak Arts Council. The Slovak Arts Council is the main partner of the project.