Gem of the Slovak sculpture scene – Juraj Bartusz in his art studio above Košice about life, war & art

Born in the southern part of Slovakia, he learnt to speak Hungarian first, hid in his neighbours’ underground basement during the WW2 and moved to Košice for work after spending some years in Prague and Bratislava. He has lived here ever since and became friends with the most prominent Slovak artists of the 20th century. Today, whether you are a local or a tourist, you will certainly pass by one of his sculptures. Most likely the one in front of the St Elizabeth’s Cathedral. Talking and reminiscing about past regimes and the art of sculpture, this is Juraj Bartusz, a Košice-based sculptor.

The Bridge in Štúrovo still stands

Juraj Bartusz was born on the 23rd of October 1933 in a South Slovak village Kamenín which belonged to the area that suffered one of the worst WW2 casualties. The village had a strategically important position due to an iron-concrete bridge across the river Hron connecting two countries, Slovakia and Hungary in Štúrovo.

“All of the other bridges to Budapest were destroyed but ours was being protected by both sides, the Russian and the German. When one side didn’t advance, the other did and vice versa. The whole area was heavily affected and not a single house remained as it was. We had to hide in the basement of our neighbours since our family didn’t have any. The area around Kamenín is considered one of the bloodiest in Slovak WW2 history. I, too, was shot to leg and arm on my walk for the water to the well. My family survived, but we were lucky. The bridge in Štúrovo was also destroyed and reconstructed only about two decades ago,” says Juraj.

His father, stone and the concrete cutter was a huge fan of art and often talked about famous artworks to him and his brother Július. Hence, it was thanks to the father that young Juraj, who at that point spoke only Hungarian, that he applied for school in Prague. Here he studied for the next few years at UMPRUM – Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design (1954 – 1958) and at the Academy of Visual Arts (1958 – 1961) to become an academic sculptor.

Gagarin and promotion department at the East Slovakian Steelworks

After his studies, Juraj married his schoolmate Mária Vnoučková – Mária Bartuszová (1936 – 1996) who also created numerous sculptures scattered around Košice neighborhoods. Bratislava was at that time crowded, Kamenín, on the other hand, impossible to provide means of living for a young artist. Juraj says that at that point he read an article about vacancies for a promotion department in the East Slovakian Steelworks.

“I travelled to East Slovakia after school and stayed here ever since. There was a huge apartment block construction for employees of this company, many in new suburbs such as Šaca or Furča, for them to live close to work. I and my wife Mária lived in both of these areas,” explains Juraj. Later in 1966, the first man in the open universe, Yuri Gagarin, visited the second largest city of Slovakia and the enterprise East Slovak Steelworks.

“Originally, Gagarin was a founder, that’s why he wanted to see such large premises. His first foreign travel led to Košice, I saw him just from the distance on Main Street, nobody could take pictures. Gagarin was very short, that’s the reason he was chosen for the expedition. I created a Yuri Gagarin Memorial (1975) in his honor to be placed in Šaca.”

Read also: World-class artist – the life of a sculpture legend Ján Mathé from Košice

The portrayal of Július Jakoby

Short-sighted socialistic realism

After his work in East Slovakian Steelworks, Juraj Bartusz worked as a free-lancer. This period was characterized as an art epicentre for artists not only from Košice – thanks to a small percentage for visual art pieces for each new construction, a lot of opportunities made it possible for many artists to move to Eastern part of the country. The socialistic regime, however, accepted only those who followed a strict doctrine which did not use any abstract or spiritual features. Juraj was investigated for a forbidden art exhibition in the year 1973.

“They asked me who I met with. Afterwards, they commanded not to employ me, not to give me requests for new sculptures. It was short-sighted from them, though, they didn’t have any clue we had other contacts outside of Slovakia. A friend of mine from Prague offered me his house and studio so I could work on my sculptures from there. I built myself my own studio in Košice. I formed monumental pieces and needed light and space. Artists of the socialist period were not just parasites – thanks to a lawfully established part for visual art in new neighbourhoods they had new orders and things to do.”

The East Slovak Gallery’s poster by Juraj Bartusz (1966)

The portrait of a close friend and a poet Egon Bondy

Deeper sense requires talent

When asked whether he could imagine his lifetime oeuvre without his studies, Juraj answers honestly – creating artworks for public space and remaining in art scene demands academic knowledge, an effort to learn as much about the particular discipline and its history as possible. He also mentions that looking back at his sculptures doesn’t bring him much pleasure, yet Juraj feels glad and proud that he does not stand behind any poor-quality piece.

“When I see those sculptures, I see that from a critical point of view. Some things I like more and some I would now do differently. To create some low-class piece will always turn out badly for the designer, it will bring a negative outcome eventually. I am not in love with the sculptures I made a long time ago, however. I was always interested in the thing I was working on at that moment. Now it is Marián Varga’s (Slovak musician) bust.”

“If you want to devote your profession to something you don’t have a talent for, it will only become your misery. To make your art have meaning, you need to strengthen the talent with education which will make you understand all the necessary issues. It’s as if I was trying to be a poet.

An artist can put his/her own soul into the piece, something from the inner self, that and nothing more. Temper, spirit, a feeling. Nobody can transform into somebody else. That’s impossible. If you admire someone and you want to act the same way, it will never come out naturally. Simply, you have to be yourself.”

Current work – the portrait of Marián Varga (Slovak musician)

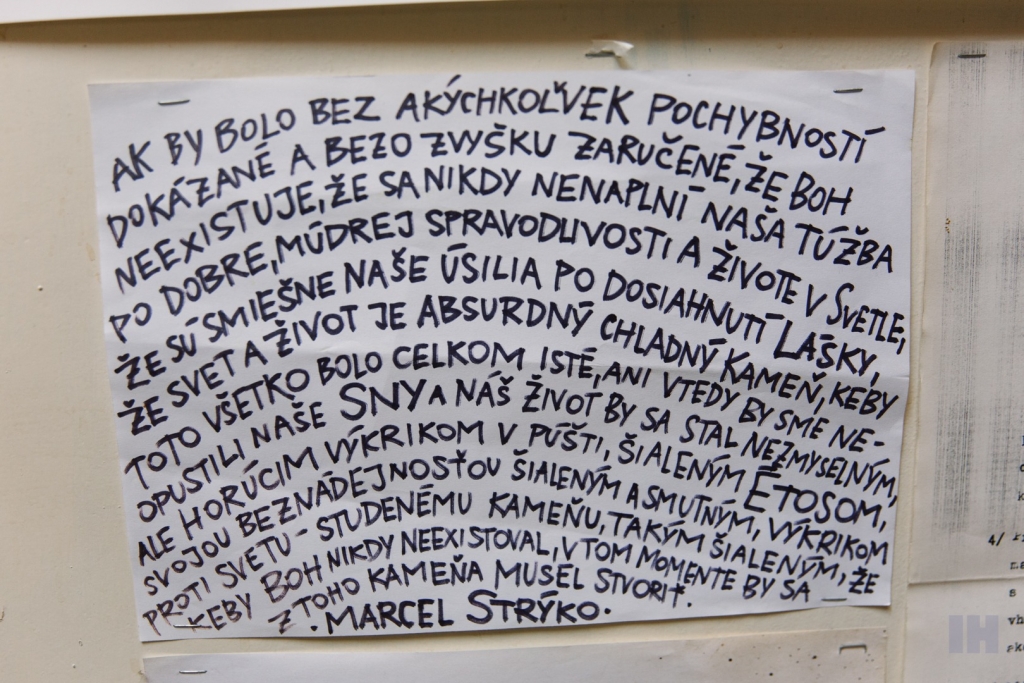

A gift from a friend and a poet Marcel Strýko

The artsy elite of Košice

Everyone who knows Košice at least just a little bit has surely passed a standing man with a hand hidden behind his back on Alžbetina St. This is a famous sculptural portrayal of the painter Július Jakoby who became a close friend to Juraj Bartusz during his life and, moreover, required a weekly visit which had to be explained if not fulfilled.

“We were friends and talked about everything. He had that special kind of an art craze which wasn’t very often. When I missed a visit, he was furious, he was really hard to get along with from time to time. I called Július Jakoby to his portrayal only once it was embedded on the street. His left hand was undeveloped so he was hiding it behind his back and a food-bag. He came up to the sculpture, walked around it, and explored it from all angles, then he said ‘It’s not a beautiful sculpture, but it’s a good sculpture!’,” laughs Juraj.

According to him, Jakoby did not praise much, yet he remains one of the most iconic and important artists in the history of art in Košice. Juraj was friends with Ján Mathé, Vojtech Löffler, Ľudovít Feld and also a well-known poet Egon Bondy.

Juraj Bartusz was the first professor with the academic degree who founded the Faculty of Arts at Technical University in Košice. He led the Studio of Free Creativity at the Academy of Fine Arts & Architecture in Bratislava, was a member of the Concretists’ Club and the Association of Hungarian artists in Czechoslovakia. His art pieces are displayed in the National Gallery in Prague, East Slovak Gallery in Košice, Slovak National Gallery in Bratislava. He is the author of Andy Warhol’s Fountain in Medzilaborce or The Memorial of Revolt in Krompachy. He lives and continues to create in Košice with his wife, a writer Jana Bodnárová.