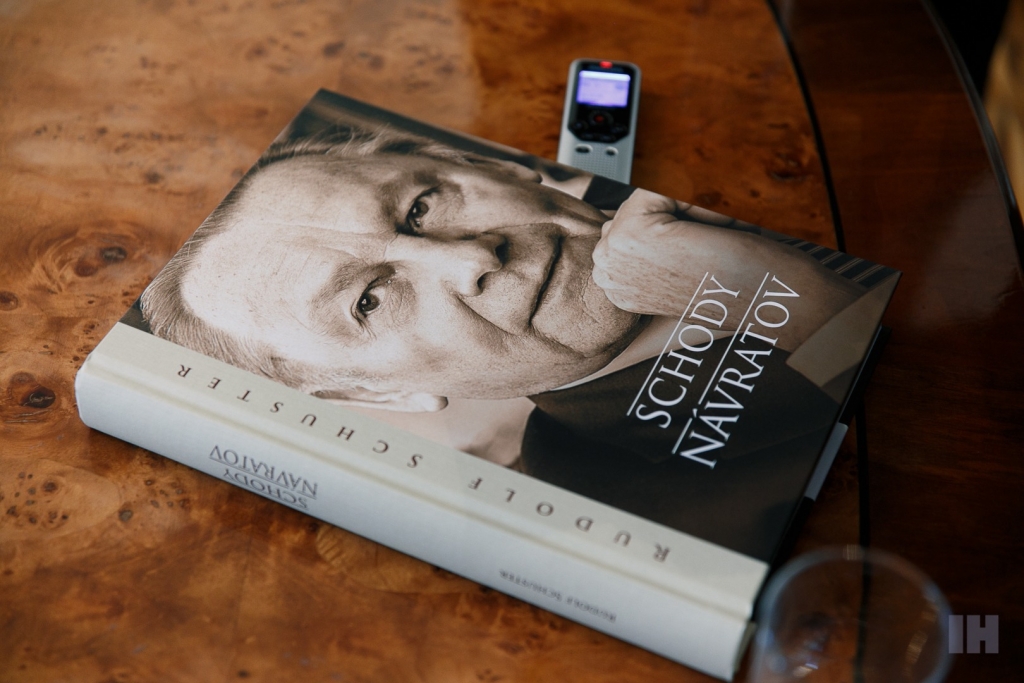

12 questions for the former President of Slovakia, Rudolf Schuster, on endurance, rebellion & compassion in Košice

A name which is associated with a lot of professions, Brazilian documentaries, books, strong political activity, Košice Main Street, Arctic & Antarctic photography, and even Italian stone pavement. A revolutionary who has transformed the Eastern Slovak metropolis into what the city is known for today. How does this famous Medzev resident reflect on his hard work today? What has shaped him as a little boy to become successful? What are his most heart-warming memories of Košice? These are twelve questions for the former Mayor and President of the Slovak republic, Rudolf Schuster; his answers explain his everlasting perseverance, compassion and universal tips for effective business.

It is widely known that you’ve done and achieved a lot of things in your life. What or who has motivated you in your endeavours?

To be honest, I have always been influenced by the environment I was born into. I come from a small village near Košice, Medzev; here, Slovak, Hungarian and Carpathian German families lived together. Our family was of Carpathian German origin and belonged to the blue-collar working class; of which my father was a great supporter and admirer. He was a great example for my future, he was fair, honourable, devoted. My father was praised by everyone and he always fulfilled what he promised. I learned the endurance from him and not to make promises I could not keep. I wanted to pursue my dreams and work in a theatre and play football, but my father explained to me the importance of studies, especially in Slovak schools. Thanks to his insistence, I became the first secondary school graduate and the first engineer in Schusters’ family. That was a starting point for the success I achieved later in life.

After completing your university studies in Bratislava, you ended up in Eastern Slovakia once again. Has this affected you in any way?

My identity always emerged from our family, Medzev and Košice. Surprisingly, I moved back to Košice because I and my wife were able to get a new apartment there – as a supporter of Alexander Dubček and his progressive ideas, I was transferred from the East Slovak Ironworks to the position of a Vice Chairman of Municipal National Committee for Services. I was supposed to reside there for only one year but the supervision continued to prolong my stay since the city started to change for the better. I tried to notice every single thing about Košice, I needed to know everything about it. That turned out to be my destiny later – first, I was a Vice-Chairman, then a Mayor, Chairman of the Regional National Committee and later I became the first Speaker of the National Council of Slovakia. I always supported the idea that you should be judged only by those who know you, those who live where you do. I decided to stay in Košice and got elected once before and twice after the Revolution of 1989. If I had done something which would go against the interests of Košice’s residents, they surely would not have voted me in. I lived here and stayed. They knew everything about me.

What was closer to your heart – to work as a Mayor or the President of the Slovak Republic?

I must say that being a Mayor had a stronger impact on me personally. In Košice, I could be aware of what was going on in the city on a daily basis. A number of innovations I brought met with disapproval and sometimes protest from the leadership; it was only when they saw the support I had from the citizens that my proposals were given way. This was the case with live-streams from the Municipal Council’s sessions, for example. It was similar to some of my other proposals, such as the celebration of Košice City Days– since we received no money for its first year, we needed to organize its preliminary year. We didn’t just want to celebrate, though, our goal was to show the citizens what we have done in the past year. My idea was heavily criticized but when I saw 20,000 in the streets, I knew that what I fought for was the right thing. Košice residents wanted to see the changes. The same happened with the renovation of our Main Street – people became ecstatic when they saw the new beautiful facades.

The public knows you as a President, Mayor, Prime Minister, writer, traveller, photographer, cinematographer, singer, tennis player and playwright. Did we forget to mention any of your hobbies or previous occupations?

I think you have named them all. I would say I am an amateur in everything except for my degree in civil engineering.

What does the city of Košice mean to you?

Košice is the most endearing and desired place for me. I was born, studied and graduated from high school here. My kids were born in this city and I spent the best years of my life here. It was amazing to see how Košice transformed and to experience the gratitude of my voters.

What is your best memory of the city?

I must say that it was the process of reconstruction of Main Street. In 1996, I very much wanted the International Peace Marathon to take place directly on it. It was raining a lot during that year, and I even invented shelters so the builders could work in the rain. Finally, the marathon was held there and even the committee came to see it. I also have wonderful memories of the above mentioned Košice City Days and more specifically, when we handed over the space of Main Street to the public. The most impressive moment, however, was when I was elected the President of the Slovak Republic and I had to give up my job as a Mayor. Thousands of Košice locals came to say their goodbyes to me and my wife. I had a farewell speech and we both had tears in our eyes. We didn’t want to leave. We knew it would be different in Bratislava.

Of all the things you have improved or changed in the city – which are you most proud of?

There is not one specific thing I have in mind. First and foremost, I wanted the city of Košice to be recognized as a heritage site, but until the same happened for Bratislava, we could not expect it. I started the reconstruction based on old photographs of the city. It took such a long time to register the city as a heritage site that we managed to reconstruct the whole place in the meanwhile. I had the original fences, lamps and lanterns made, I copied the vases from abroad. Most of them were donations from the East Slovak Ironworks, even the 5.2 ton Urban bell was cast there. During my visit to Austria, I was enchanted by an Italian porphyry stone – Salzburg’s pavement was laid with it and on its place for nearly 130 years now. I decided to hold a stone contest for new paving in Košice, but, surprisingly, the Slovak stone was more expensive than the Italian one. We ordered so much of it from Italy that they came to take a look at what we were doing here. When they counted 70 pavement tilers working at the same time, they congratulated me. Later, people from Prešov wanted to order the same stone. But they needed to wait until we finished our paving in Košice so that the Italians could cope with it.

How would you describe the city in three words?

Beautiful, attractive, impressive. It must captivate you, the city environment must live in symbiosis with its people. Before reconstruction, the streets in the city centre were empty after 6 PM due to safety concerns, the park was not visited at all. Before I made my Mayor’s promise in 1994, I bought new Christmas decorations. They immediately wanted to dismiss me. Yet, thousands of people came to the city to see the first Christmas decorations in Czechoslovakia. It really feels good when someone continues your tradition. It doesn’t matter if you were the first one to invent something, but whether the change catches on. For example, I had the walls of the Košice Castle dug up and we organized knights’ festivities there. When we knighted old Tomáš Baťa (founder of a famous shoe company), he cried. US Congressman John Mica, on the other hand, a friend of George Bush, said he had never experienced a bigger celebration in his life than he did in Košice. It was very important for me to establish personal relationships, and later, as President of the Slovak Republic, I was welcomed everywhere. It helped me during many negotiations.

What is Rudolf Schuster’s Achilles’ Heel?

The weakness of Rudolf Schuster? I admit, if somebody used their emotions against me, I often agreed to what they were asking for. I’m just a human, compassion usually overwhelmed me, especially if someone needed help. So I ended up being used by many people. Although I was firm in my decisions, some things came back to bite me.

It is known that you went on many expeditions. How has travelling changed you?

As a child in Medzev I was always known to have the first flowers that blossomed in the village. Since then, I have lived intertwined with nature and I knew all the hiding places of snakes, frogs and birds. I knew my surroundings, but I always wanted to go further. During our family vacations, I filmed and documented everything. Nevertheless, I longed to continue in my father’s and uncle’s footsteps who were pioneers with their Slovak documentary about Brazil in 1928. Later, when I was an Ambassador of the Slovak Republic in Canada, I succeeded – I made seven documentaries about my travels in Brazil which were later broadcast on STV1. I returned to Brazil several times after that, most recently with my granddaughter as the fourth generation of the Schuster family. Then I started to visit more extreme places like North and South Pole, Alaska, Kamchatka, Chukotka. Afterwards, each destination got its own book and a film – a report about Svalbard is being prepared right now. Travelling meant a new perspective, learning, a broader context. For example, I have seen global warming firsthand. The places I filmed before were flooded with water when I returned to them years later.

Which personality you’ve met was the most impressive?

There was certainly more than one – Johannes Rau, Heinz Fischer, young George Bush, Carlo Azeglio Ciampi just to name a few. I had a close relationship with them; for example, Ciampi wanted to come and see my home in Medzev. There was nothing else left to do but to invite him. Aleksandr Kwaśniewski, who helped Slovakia when we were not yet in NATO, but the V3 members were, was also a close friend of mine. If a president or politician knows several languages, it’s a great advantage. I dealt with Germans, Austrians and the Swiss in German, with Hungarians in Hungarian, with Russians in Russian and with the rest in English. You can do without a translator then. Four eyes are really not the same as six.

Does the city of Košice hold a record in the Guinness Book of Records for the highest number of people dancing Macarena at the same time?

Yes! More than 70,000 people danced it on Main Street. We closed the street with the help of the police. I was afraid there would be some kind of accident. It took place in 1997, but since then we haven’t really found out whether someone has beaten us.